The first few times I delivered a territorial acknowledgment in a professional setting, I went about it the way I’ve learned to approach all professional presentations: I prepared obsessively, looked at as many official-seeming examples and templates as I could find, and then crafted and recited a statement that felt polished and rigorous. This is, after all, how I’ve learned to do my job well.

But when fellow non-Indigenous colleagues thanked me for the “beautiful” acknowledgment, that’s when I realized I needed to do much better.

In this piece, I offer a set of prompts and guidelines for settlers and others who are new to acknowledging Indigenous lands in academic settings. I use “settlers” here as a shorthand for anyone living on colonized land whose genealogy does not include Native kinship to the land, with the caveat that it is important to recognize how Indigenous communities define their genealogies and community affiliations, as well as the vastly different ways that non-Native people have arrived on Indigenous lands. Jodi A. Byrd, drawing on Kamau Brathwaite, has proposed the term “arrivants” (a term taken up by other scholars including Tiffany Lethabo King) to distinguish the descendants of enslaved African people and refugees who have been forcibly driven from their homelands by imperial war from descendants of European settlers claiming Native land as property. Considering the pathways by which you, personally, have come to be here and how your presence fits within these arrangements of power is part of the work of land acknowledgment.

I offer the following thoughts as a student of these practices, not an authority on them. I can’t tell you “how to do a land acknowledgment,” nor can anyone; instead, I can share what I’ve learned in order to help us think together about the work we are being asked to do and how we can do it responsibly.

First: is this something we should do?

Yes, I believe it is. Why? For one, because acknowledgments are already a part of our practice. We routinely recognize our colleagues, our mentors, our funders and fellowships and societies and institutions—anyone who has supported our work and made it possible—to express our gratitude and indebtedness to them. It’s a valuable way of situating our intellectual contributions within the broader structures and networks of relation that enable us as scholars, and, crucially, it names the bodies to whom we consider ourselves and our work accountable.

But where we and our work are—the land not just as site but as our active situation, determined by the Indigenous communities who belong to the place; the treaties that protect the land and the relationships it sustains; and the histories of dispossession and extraction embodied in the land’s “development” into a site that upholds, among other things, our scholarship—has not traditionally been part of the professional ritual. Thanks to the sustained efforts of Indigenous communities and people working in Indigenous Studies, Ethnic Studies, anticolonial studies and movements, and bodies such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, academic institutions have been clearly called upon to reflect on these particular webs of relation and accountability. Learning how to practice acknowledgment of the land is a first step in responding to this call.

So the practice we call a “land acknowledgment” is really a site-specific exercise in reflective self-awareness: Where am I right now, and with whom? How have we come to be here, and for what purpose? To whom does this place put me in relation, and on what terms? To whom am I accountable here? And how will I act, and orient my work here, so as to meet my responsibilities?

Is there a script or template?

Some institutions have made these, but many members of Indigenous communities have insisted that acknowledgments that sound formal and scripted do not do the necessary work of illuminating relationships of responsibility and calling people into them. In fact, formal acknowledgments tend to have the opposite effect, offering some solemn-sounding words that the institution and its representatives can recite instead of making sustained efforts at being in good (or at least better, and improving) relation with the land and the peoples connected to it. Discussing his regrets at helping his home institution, Ryerson University, with a formal acknowledgment several years ago, Anishinaabe scholar Hayden King explained, “the territorial acknowledgement is by and large for non-Native people. So if we’re writing a script then providing a phonetic guide for how to recite the nation’s names … it doesn’t really require much work on behalf of the people who are reciting that territorial acknowledgement. It effectively excuses them and offers them an alibi for doing the hard work of learning about their neighbours and learning about the treaties of the territory and learning about those nations that should have jurisdiction.”

Therefore, if you decide to make an acknowledgement of our collective situation in this place—the people, treaties, histories, and responsibilities that determine it—you should craft one informed by your own efforts to learn the names and histories of the place; the peoples, languages, lifeways, and diplomacies that primarily belong to it; and how you come into relation with all of these by being here, now.

Cultivate an idea of what you’re trying to do through the work of acknowledgment, and then learn how to do that. It’s a deep and ongoing process.

Ok, but can you offer any pragmatic tips?

Lots of folks have. Start here:

https://native-land.ca/territory-acknowledgement/

https://nativegov.org/a-guide-to-indigenous-land-acknowledgment/

https://apihtawikosisan.com/2016/09/beyond-territorial-acknowledgments/

Other things to consider:

An effective acknowledgement should include:

-

- Recognition of the Indigenous nations on whose traditional and ancestral lands we are presently gathered, as well as nations with other meaningful connections to the place

- Recognition that we are gathered in this place as a result of its colonization

- Recognition of the treaties in effect on the land, to what extent they are being honored, and Indigenous nations’ efforts to enforce them (for example, movements to block oil pipelines and other industrial developments that violate sovereign territory and/or protected hunting grounds)

- Recognition that the Indigenous nations connected to this land, and forcibly displaced from it by colonization, are still here, and that these living connections need to be honored and restored—literally restored, as in giving the land back

- Recognition that honoring these relationships requires ongoing learning, work, and commitment, and that our scholarship can and must be part of that work

- Indication of some way those of us gathered at this conference can pursue that work in our scholarship

- Indication of how we can contribute directly by donating money to and amplifying the voices of local Indigenous land protectors

The acknowledgment need not be lengthy in order to include all of these elements, just focused. And it doesn’t all have to be contained in a prelude to your presentation—as I discuss in more detail below, your acknowledgment should both frame and weave its way into your work. Your presentation itself can acknowledge where it is and what it owes to this place. YOU, in the way you approach the conference as a chance to think with others, can make these acknowledgments part of how you make yourself present.

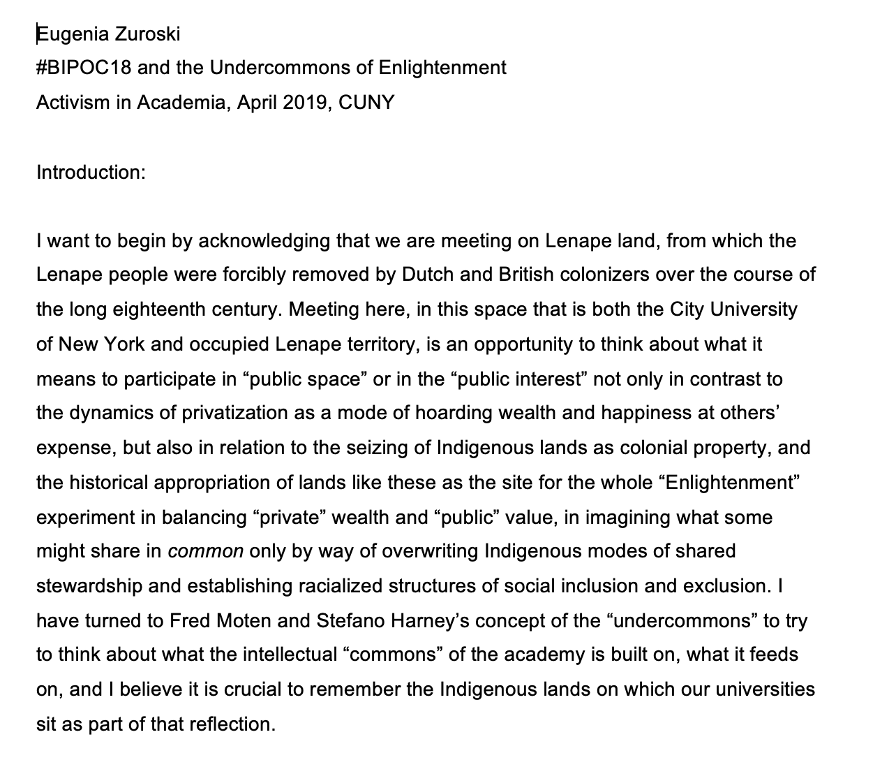

At the end of this piece, I’ve attached some images of my “acknowledgment notes” from two talks I gave in New York City last year as examples of how I’ve tried to approach this. They are mere examples, not exemplars.

I’ve also tried to demonstrate in my “acknowledgments” at the end of this piece how our conventional academic acknowledgments can be directed toward honoring the land we are on, as well as the people we think with.

Being in good relation means knowing what you ask of people.

As you work on your acknowledgment, be cognizant of how you ask for help as someone in the process of learning from others. Settlers habitually struggle to navigate the boundary between recognizing the authority of Indigenous knowledge and demanding access to that knowledge when we decide we have need of it. While it is a settler’s responsibility to learn, it is not the responsibility of Indigenous people or communities to teach us. How, then, do we respectfully proceed? There are many resources. Do the reading. Listen (without speaking!) to conversations already in progress in places like Twitter. Make use of the wealth of information that has already generously been put into circulation, some of which this article links to.

At some point, it may become appropriate to consult—respectfully—with the communities you wish to acknowledge. Once you’ve drafted an acknowledgment for a conference, for example, you might reach out to the hereditary chiefs, community elders, or governmental offices of the nations whose traditional territories you’ll be visiting, to say that you’re working on a land acknowledgment and want to make sure you are using wording that they prefer; you might also ask whether there are other nations and communities that should be included. Carefully consider existing protocols of consultation through these pathways. You could also reach out to members of Indigenous Studies programs in the area, or colleagues you think might have insight into the acknowledgment you’re making.

With any of this outreach, always recognize that every email you send seeking input is a request for someone’s labor. Are you asking for it on fair terms? Do you have something to offer in exchange? Asking informed questions is an important part of the process, as is centering the knowledges of Indigenous communities, but it’s important to remember that no one is obliged to answer you. Learning to ask questions without expecting immediate or direct answers is part of settler pedagogy.

You are literally here.

Are you familiar with the phrase “decolonization is not a metaphor,” the title and declaration of Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s vital article? Like other kinds of professional acknowledgment (your grant, your co-author, your mom, etc.), your acknowledgment of Indigenous land names a literal, not a metaphorical, relationship. You are literally and materially beholden to this place and its communities for enabling you to be here and do whatever it is you’re doing. Is what you’re doing consistent with your obligations here? How can you make it so? And, crucially, how can you practice land acknowledgment in a way that doesn’t turn it into a “settler move to innocence” (Tuck and Yang) that disavows these obligations?

An acknowledgment frames your way of knowing and what it does in the world.

Don’t distance the act of acknowledgment from the content of your scholarship; weave them together. How does presenting this work on this land frame particular questions or concerns? How does the work contribute not only to the academic field but to the project of being in good relation with the people connected to this place? These are particularly pressing questions for our field of eighteenth-century studies, which encompasses the historical period in which European colonization intensified to a global system. There is nothing from the eighteenth century to which the history of colonization is not relevant, and that history generates a web of present relations that demand our attention. By routinely acknowledging the land, its people, and ourselves as part of its history, we can draw crucial connections between the knowledge we gather as scholars of the eighteenth century and the responsibilities we bear as practitioners in the present.

Acknowledgment is a small part of a big project.

Land acknowledgments belong to a broader body of anticolonial and decolonizing thought and practice. There’s a lot of work out there in this area; make a reading list and dive in. Some colleagues and I made this resource list for a workshop we organized last fall at McMaster, located on lands protected by the Dish With One Spoon wampum agreement, the traditional territories of the Mississauga and Haudenosaunee nations, and site of the first treaty made between a First Nation and European settlers on Turtle Island, the Two Row Wampum. You could start here, but also recognize that with such site-specific learning, your own reading list may best draw on bodies of knowledge situated nearer to where you are.

Feeling ill at ease is central to the work.

Acknowledgment is an act of unsettling and, to a settler, it should feel unsettling. You are learning how not to be (in the) “right” where you are. Therefore you must fight all your professional urges to appear polished and authoritative in how you do it.

This brings me back to my own early attempts and what I learned from them. We are trained to assert ourselves as experts when presenting our scholarship, to command respect by performing the knowledge we possess and our mastery of it. But the act of acknowledging land to which you are not Native runs counter to the dynamics of mastery; you are placing yourself in relation to what you don’t know, what you don’t possess, what you shouldn’t claim, what you are connected to and responsible to for reasons beyond your control and full comprehension. As Métis scholar Chelsea Vowel writes, “territorial acknowledgments … can be transformative acts that to some extent undo Indigenous erasure … as long as these acknowledgments discomfit both those speaking and hearing the words.” The use of these lands by settlers to practice “professionalism,” to claim expertise that erases Indigenous knowledges, and to consolidate capital for colonial institutions through our intellectual exercises—these are fundamental colonizing practices that are part of what we are being asked to acknowledge, confront, and divest ourselves of.

In acknowledging the land, you acknowledge your own alterity to it, and your need to account for your privileges on it. If that doesn’t make you uncomfortable, you aren’t fully engaged.

I am by nature an anxious and obsessive over-preparer for professional presentations. I don’t always read from a script, but until recently, I always prepared one, for any shared remarks. Lately I have begun challenging myself to make my land acknowledgments “off the cuff,” using only the resources that arise within me in the moment, from the knowledge I’ve gathered up to that point. There is still lots of preparation—all the homework described above, practicing the pronunciation of names and terminology, reflection on how historical placement conditions the work I have to offer. But instead of writing or memorizing a script, I challenge myself to think through the acknowledgment in the moment I make it, as a way of being fully present in the act in an honest and vulnerable way.

It always leaves me feeling exposed and inadequate: that I could have articulated something better, that I pronounced something wrong, that my way of accounting for how my work might contribute meaningfully to Indigenous life was dubious and painfully sketchy. I always feel like I could, and should, have done better. And that feeling, as excruciating as it may be, is true to the practice. Our acknowledgments will always, necessarily, be inadequate to the task of addressing how deeply and violently colonization has implicated us in one another, to the task of answering fully for what must be repaired. They are, by definition, an acknowledgment that we can and should do better by one another.

And they position us to recognize how we and our scholarship can help create the conditions under which we will do better.

————————————–

I offer thanks to all the people whose ideas and expressions of support are part of this document. In particular, in addition to the people cited in the piece and my colleagues in Indigenous Studies at McMaster, I thank Megan Peiser (Choctaw Nation), Natalee Kēhaulani Bauer (Kanaka Maoli), and Griffin Epstein for sharing their knowledge here. This piece was written in my house on colonized Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee land, the Dish With One Spoon. I recognize the dubiousness of my right to share in the dish and my obligation to protect others’ rights to it. If this piece gives anything to you and your work, I ask you to consider giving back in one or more of these forms: 1. Cultivate a literacy in wampum belts and help me learn how to honor the wampum treaties that protect the land we’re on; 2. Support Wet’suwet’en land protectors by donating to their legal fund; 3. Donate to the Back 2 the Land: 2Land2Furious LandRaiser organized by Chelsea Vowel; 4. Support land protectors at Mauna Kea by donating to the Kahea Legal Defense Fund; 5. Support Indigenous political prisoners and their efforts to protect Standing Rock and other waterways by donating to the Water Protector Legal Collective; 6. Support land protectors in many areas by donating to the Native American Rights Fund; 7. Learn about an Indigenous land protection or land back movement in the place where you live and work, amplify it, and donate to it.

Appendix: Two images of attempts of the work, in progress.

Eugenia Zuroski, McMaster University